Supporting Graduate Student Working Conditions is a Matter of Educational Equity: A Letter to the UIC Community

Andrea Daviera

March 28, 2022

Photo Credit: Elias Kassa

Dear UIC community,

You may not know me, or maybe you do. My name is Andrea and I’m a member of the University of Illinois Chicago (UIC) community in a few ways. I’m a writer for Bonfire, but also a Ph.D. student in the psychology department, a doctoral candidate in the community and prevention research program, an instructor for an introduction to community psychology course and a member of the Graduate Employees Organization (GEO). GEO is the union that represents all teaching and graduate assistants at UIC. For the past year, we have been fighting to get graduate student employees a fair raise and other improvements to our contract. You may have seen our recent protest in the quad or picket outside of Student Center East. However, despite our best efforts to settle on a contract with the university, our negotiations have reached a stalemate. We have reached our final recourse. From March 30 to April 1, the union is asking for all of its members to participate in a strike authorization vote, online or in person.

I’m a fairly average graduate worker, in that I have juggled a variety of teaching and research assistant appointments to support myself financially while working on a bunch of my own research. Like many other graduate students, I genuinely love my research and the undergraduates that I teach. UIC has provided me with invaluable learning experiences as a scholar. However, I’m also an average UIC graduate worker because, during the nearly 5 full years that I have worked here, I have had to manage with low pay, financial insecurity, and inconsistent employment, which I’ve dealt with while financially supporting my parents. This is because I’m the first person in my immediate family to go to college, and the COVID-19 pandemic was disastrous for my parents’ abilities to support themselves financially, buy food, or pay the rent. But this letter isn’t just about me – I am only one worker out of thousands of graduate students. When working-class students like me struggle to make ends meet, doing a dissertation, teaching a class, or working on a project is just difficult or impossible, and sometimes, leaving the university without a degree is a better decision for our financial and emotional wellbeing. All these reasons are why I’m writing this letter. I need you to understand that supporting graduate student working conditions is a matter of educational equity.

What does “equity” mean or look like in higher education? This word is used often. There is growth and popularization of the canonical “diversity, equity, and inclusion” (often shortened to DEI). There are many well-intentioned folks who are highly invested and committed to promoting DEI in their workplaces, including UIC. Most of us know that UIC is considered an exceptionally diverse campus and is a designated “minority-serving institution.” However, as a researcher trained in community psychology – a field that emphasizes an appreciation for diversity in its approach to addressing social injustice – I have to ask, diverse for whom, and where is there meaningful representation?

We may see racial-ethnic diversity in the undergraduate student body, for example, but this starts to lessen as you begin to move up the academic ladder. According to UIC’s data, the undergraduate student body is roughly 34% Latinx students and 20% Asian students, but only 8% Black 7% International students, and 5% “other,” compared to 26% White. At the graduate student level, these numbers shift. According to data from UIC’s Office of Institutional Research (OIR), 35% of graduate students are White and 28% are International, while only 13% are Latinx, 9% are Asian, and 9% are Black. OIR’s data shows that the faculty body is even more White – 58%, with the remaining population being 20% Asian, 7% Latinx, 5% Black, and 3% International. This data demonstrates that the representation of some people of color increases or decreases at each step of the academic ladder. Most notable, the proportion of White individuals to non-White groups increases dramatically between graduate student and faculty status.

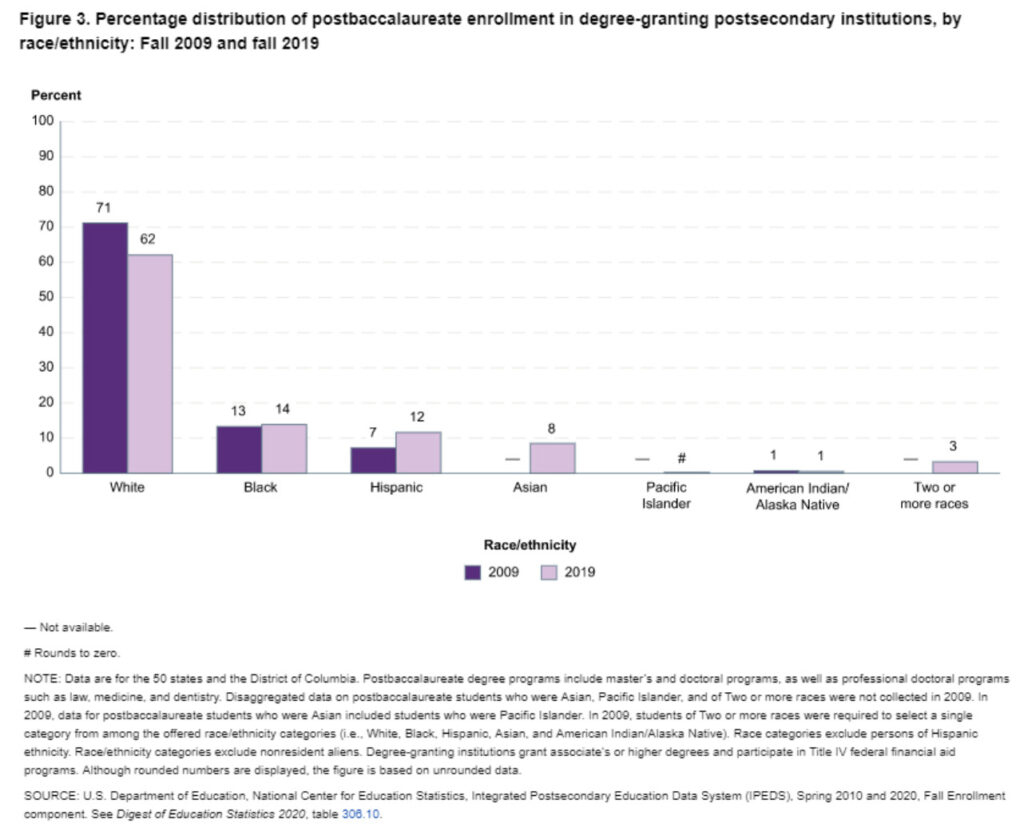

We can see educational inequity widen when comparing racial-ethnic representation at different levels of UIC’s hierarchy, but unfortunately, this pattern exists at most higher education institutions across the country and is even more disparate. According to the National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES), 62% of students enrolled in postbaccalaureate programs were White, and 75% of faculty.

Image 1: Postbaccalaureate Diversity In the United States

Image 2: Faculty diversity in the United States

The fact remains that despite many efforts to increase DEI in higher education, there is still a lack of it, particularly as we compare people who hold different roles – and therefore, relative power and influence – within the minority-serving institution. While UIC verbally commits to supporting DEI, if those achievements are measured by racial-ethnic representation across different places within the power chain, it is telling that you see less diversity as you move up the ladder. In particular, we see that fewer Black and Latinx students are making it to and through graduate school. Research indicates that this is because graduate school is a challenging career stage and can be particularly difficult for those who have been historically excluded from higher education. “Exclusion” is purposeful language that makes the recognition that the lack of diversity in higher education has been intentional, formally or informally coded and enforced. Exclusion doesn’t just affect students of color, but those who identify as LGBTQIA+, women, first-generation, lower-income, undocumented, immigrant, international, and disabled. There are a variety of reasons why graduate school is so challenging, But while classes may be tough, research may be stressful, and the days may be long, what makes graduate school most challenging, and particularly inhospitable for students who have been historically excluded, is that graduate workers face chronic financial insecurity, employment precarity, and exposure to harassment, bullying, and discrimination.

First, there is simply a lack of financial security, and students who are non-White may have less financial capital prior to entering graduate school. White students and those whose parents have college degrees often arrive at graduate school with more generational wealth and social capital. Their families may be better able to offer financial or material support. On the other hand, historically excluded students who lack generational wealth may have little financial and material support from their families, or may even be supporting their families, like myself. This financial struggle is even more pronounced at UIC, which despite the increasingly high cost of living in Chicago, pays its graduate workers the lowest salary in the city.

Despite the fact that I work the maximum amount of hours that I am allowed to work as a graduate student (which is 67% full-time employment), not having a living wage impacts me directly, as groceries are steadily becoming more expensive, my rent increased last year (and possibly will again) and my credit card and student loan debt continues to accrue. Being unable to save money impacts my ability to support my family financially. I do what I can, whether it’s groceries for my dad or paying my mom’s phone bill. But the support I get from UIC just is not nearly enough. Again, this doesn’t just affect me and my family, but all graduate students, their dependents and their loved ones.

Financial insecurity is exacerbated by the exorbitant amount of fees that graduate students pay the university. Graduate students at UIC pay approximately $2,000 per year. These fees, including a “General” fee, library fee, service fee, and others, are assigned to us because we are students but they increase regularly. Egregiously, these fees make grad workers pay approximately 10% of their salaries back to the university, a practice that many labor rights organizers and advocates identify as “wage theft.” What other employees have to pay their employers to work at their jobs? Notably, Graduate Students United, the grad worker union at the University of Chicago, recently won fee elimination after a successful “fee withholding campaign,” where graduate students collectively stopped paying for them.

How do graduate students deal with financial insecurity? Despite it generally being discouraged and not even allowed for international students, graduate students sometimes take on work outside of UIC. Whether it’s “gig work,” adjunct teaching, consulting, or something more informal, this labor takes away our time from our classes and research. Working extra hours and side jobs makes it a challenge to excel and persist in graduate school and often leads to burnout. This may create further inequity because the students who tend to be the most financially burdened in graduate school tend to be minoritized in other ways as well, and these multiple stressors may lead students to leave graduate school in hopes of finding more stable income.

Photo Credit: Elias Kassa

Financial insecurity in graduate school is accompanied by employment precarity, i.e., not having consistent or secure employment. Graduate students at UIC are required to create their own concoctions of teaching, research, or graduate assistant appointments every semester and summer. Funding is not always guaranteed, and the availability of employment changes over the course of the year. This means that one’s income can change over the year. If a graduate worker is employed at 50% full-time (that’s approximately 20 hours a week) in the fall, there is no guarantee that they will have a similar appointment next semester; it depends on what they are able to secure for themselves. Employment precarity is particularly threatening for international graduate students, who have limitations on what types of employment they can receive and how much they can work. For me personally, employment precarity affects my ability to consistently pay for my “cheap” apartment. I may work 67% full-time right now in the spring semester, but I will likely only be able to work 50% in the upcoming summer months, meaning that I will earn hundreds of dollars less during those months.

Lastly, working conditions don’t just include the physical environment we work in or the material things that we do, but also include the interpersonal relationships that we have to navigate. Relationships between a worker and their supervisor – who may also be their adviser or chair of their dissertation committee – can become toxic, like other relationships. But this toxicity is strengthened by the power dynamics at play. Graduate workers will often have relatively less power compared to their supervisor or advisor, and thus sometimes these relationships expose graduate students to bullying, harassment and discrimination. While I myself have been fortunate enough to have a supportive advisor, unfortunately, I know far too many other graduate workers who have not had such luck. Harassment, discrimination and bullying are immensely worse for graduate students of color and others who have been historically excluded. Even in a “diverse” environment, graduate students of color often experience micro- and macro-aggressions, leading to racial trauma and burnout. Anecdotally, almost every graduate student that I have seen leave UIC before finishing their degree has been someone of color, often because these compounded stressors were just too burdensome.

So, what do we do? Financial insecurity, employment precarity, discrimination and bullying at UIC create hostile environments that impede success in graduate training. GEO’s response has been to organize and bargain for a contract that would address these problems. Currently, the contract’s demands are as follows:

- 10% raise each year of the contract. This would bring UIC graduate workers’ income on par with other graduate workers in Chicago.

- Eliminating all graduate student fees.

- 9-month (2 semester) appointments.

- Strengthened protections against bullying, harassment and discrimination.

The university administration’s response has been to maintain the status quo and a raise that pales in comparison to rising rent prices and inflation. Despite the fact that the union has been bargaining for a new contract since April 2021, the administration has refused to provide adequate explanations for their refusal or alternatives that would significantly improve graduate students’ working and material conditions. Based on years of experience fighting for previous contracts, GEO leadership decided that the only thing that would move this process forward is a strike authorization vote, which is occurring from March 30 to April 1, in-person and online.

What does a strike mean for the UIC community? The point of a strike, like all direct action, is to disrupt the status quo and demonstrate the necessity of our labor. If a strike was called, graduate teaching assistants and graduate assistants en masse would stop performing all of their work duties. Grad workers are 10% of the university labor force, a sizable proportion, and we would not teach any classes, perform any administrative duties, grade any assignments, or answer student emails. The labor lost during this time would be replaced by rallying and picketing on the campus instead, trying to raise public awareness of the strike, and why we need this specific contract.

Many of us, if not most of us, do not want a strike. A strike vote doesn’t trigger a strike automatically but lets the union assess the extent to which its workers are willing and ready to strike if needed. Often, one of the best ways to prevent a strike is to have a strong and affirmative response from the grad worker community saying that they would strike if one was called, as the administration will generally want to avoid it. Affirming the strike sends a message of unity and willingness to engage in action as a step toward educational equity. The last six contract negotiations have all at least gone to a strike authorization vote, with the last one leading to an actual – and successful – strike.

Us graduate workers have an important decision to make in the fight for our right to an equitable and supportive work environment – and we will need the UIC community’s support. Therefore, I call for action and solidarity from my community.

To my fellow grad workers: please do vote yes on the strike authorization vote. Not just for yourself, but because improving grad students’ working conditions is a matter of equity, and would benefit all students, including those to come. If a strike is called, commit to refraining from work.

To the faculty body: please don’t take on grad worker duties and respect your own work hours. Support our strike (if it comes to that). Know that grad workers are not asking for anything that is unreasonable or unnecessary, but something that materially matters for our wellbeing and ability to succeed in your classes and research labs.

To the undergraduate student body: because your learning conditions are our working conditions, it is in every student’s best academic interest to have an instructor that is able to perform their job to the best of their abilities; things like financial insecurity, job precarity, and harassment are impediments to that. Know that we also do this because we hope that if and when you are in graduate school, you can support yourself and your loved ones too.

When we work together, we can win major improvements that will benefit students now and in the future. But it’s only with collective solidarity and action that we can do that. To that end, I’ll see you on the picket line.

Photo Credit: Elias Kassa