A Profile of Indigenous Organizations at UIC:

Showing Support Through Action, Education and Involvement

Ella Rappel

When Alec Joshongeva-Petersen, a medical school student at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and his fellow Indigenous colleagues began getting together to advocate for Indigenous medical school students, they knew it was part of a larger conversation about social justice and organizing.

“Native Americans are underrepresented in medical school, and we make up a very small percentage of those who actually get admitted and who actually graduate,” Joshongeva-Petersen said, explaining that medical school is a challenging environment in the best of circumstances, but especially for Native and Indigenous students due to both cultural differences and many Native students coming from less socio-economically privileged backgrounds.

In late 2019 and early 2020, in response to these challenges, Joshongeva-Petersen and a colleague in his cohort began reaching out to other Indigenous students. It was during the nationwide conversations about social justice movements in 2020 that the group officially got together under the Association of Native American Medical Students (ANAMS) label and began to organize.

“Once all the craziness of 2020 started happening, the various uprisings and such, and the renewed interest in our society about issues surrounding racial justice, we saw a very good opportunity to come together as a group,” Joshongeva-Petersen said. “Not just to support each other, but to be able to stand in solidarity with other various student groups and movements.”

As a result of the efforts of these organizers, the group won in-state tuition for UIC medical school students from any of the 573 tribal nations recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, according to the University of Illinois College of Medicine website post from Dec. 2020.

“We started meeting with a lot of administrators and… trying to get our feet in the door of a lot of places within the higher-ups of med school and med school administration,” Joshongeva-Petersen said, describing the actions the group took. “Some of our results included the UIC College of Medicine starting to publish land acknowledgments on their websites.”

The UIC ANAMS group also continued their work beyond UIC, connecting with Native medical school students at other schools such as Northwestern, Loyola and UChicago.

“We figured it might be helpful if we came together as a Chicago Alliance, just so that there were more of us and we could try and coordinate,” Joshongeva-Petersen explained. “You could say ‘did you hear? This school… got in-state [tuition], maybe we can use that to leverage our school to do something more.’”

Indigenous organizations on UIC’s campus, including ANAMS, have accomplished a lot in recent years, ranging from winning institutional changes for Native students to connecting with Indigenous communities at UIC, as well as across the Chicagoland area. These organizations are crucial resources for Indigenous students and provide space for community, action and learning experiences. Their work, however, extends beyond serving the Indigenous community; it is rooted in a story about the history of Native empowerment, student activism and community awareness overall.

Tol Foster, the Director of the Native American Support Program (NASP) at UIC – a role which he described as being “a butler of the university and its students” – emphasized that NASP is not just for Indigenous students. Anyone can participate in activities hosted by NASP and take advantage of resources that apply to them.

“What we do is something nobody else in the university does, which is that we will treat you as a relation; we will treat you as a relative; we will help you connect,” Foster explained. “Our job is to serve students in a Native way, regardless of whether they’re Native or not.”

Zoë Harris, a Graduate Assistant at NASP, explained how NASP is a way to support and connect with Indigenous students.

“It’s not just Indigenous students; obviously, that’s the focus,” Harris said. “It’s also for other students who just kind of want to learn about how they can support their Native peers.”

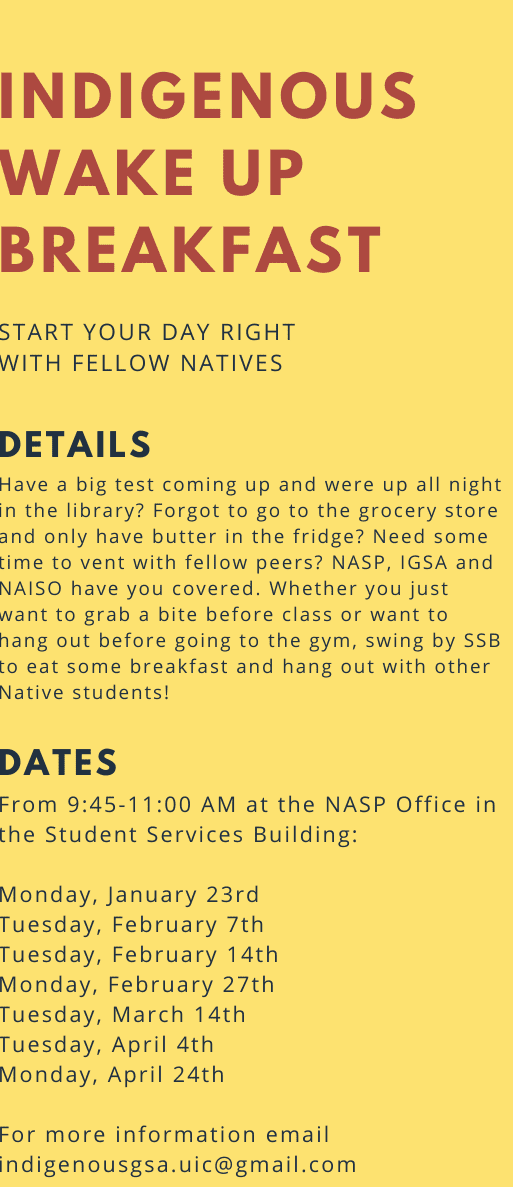

According to NASP’s website, the organization offers a variety of events and resources to undergraduate students, including advising, scholarship opportunities, and numerous cultural programming events. Foster mentioned the annual powwow that NASP hosts, as well as their ongoing free Indigenous breakfast at Student Center East that is held two or three times per month. Harris added that NASP has also organized events for moccasin making, self-care activities and watch parties for Indigenous shows.

Advocacy, networking and reaching out to the Native community in Chicago are other crucial aspects of NASP, according to Foster. Working with other organizations, be they at UIC or the city at large, is a critical way to “improve the visibility of Native and Indigenous people on campus,” Harris explained.

NASP’s partnerships include UIC’s Indigenous Graduate Student Association (IGSA), of which Harris is the President. IGSA was born after Harris’ project on Afro-Indigeneity (she is an Afro-Indigenous person herself) prompted UIC administrators and community members to consider the diverse identities of the students they serve.

“[The project] brought together a lot of administrators, in particular, to learn about how to assist students who may not identify with one particular racial or cultural group,” Harris explained. “And out of that conversation, we found that there’s really not a whole lot of support for Native graduate students.”

As opposed to NASP, which focuses on undergraduate students, IGSA focuses primarily on finding resources for graduate students, according to Harris.

“For example, people who are citizens of a federally recognized tribe get in-state tuition, but that only applies to undergraduate students through the advocacy of some medical students,” Harris said, referencing the work done by UIC’s Indigenous medical students, including Joshongeva-Petersen. “Now, medical school students also get in-state tuition, but that does not apply to people in the graduate college or professional studies.”

IGSA helps Indigenous students in the graduate college gain access to those resources. Similarly to NASP, IGSA also partners with UIC student organizations and local Indigenous organizations in Chicago to promote visibility and build community. In Nov. 2022, they collaborated with the Black Graduate Student Association on a self-care event where they obtained plants from the Chicago Botanic Gardens and talked about traditional medicine.

Collaborative events such as these for both IGSA and NASP are meant to provide “individual student support,” but also to show “the larger UIC community what the presence of Indigenous people is at UIC,” according to Harris.

Collaboration between students, their organizations, the University and the Indigenous community in Chicago has always been an essential part of NASP’s goals, dating all the way back to its formation. The “Native Americans at UIC Task Force Report” (NATF), compiled in 2021, states that NASP, originally called The Native American Program, was founded in 1970. It initially obtained financial resources after President Richard Nixon and the Department of Education “increased federal expenditures for Native American programs” in response to grassroots demonstrations by Indigenous organizers. Dean J. Kotlowski explains the demonstrations in greater detail in his article from the Pacific Historical Review.

“At the beginning, a large number of Native American activists had been shut out of higher education,” Foster said, explaining the cause of the grassroots organizing at UIC.

The organizing came on the back of the Red Power Movement, a period in the 1960-70s in which Native Americans challenged discriminatory policies and systemic injustice, discarded treaties that were created under duress and advocated for sovereignty and self-determination. As a result of the demonstrations and new policy, UIC partnered with the Department of Education and contributed some of its own money to NASP as a budding organization, according to Foster. As it evolved, the organization grew to include financial resources, the expansion of coursework related to Indigenous life and culture and an advisory board representing various community members, as listed in the NATF.

Notwithstanding this progress, however, archival documents show that “despite the obstacles and difficulties, there were more university resources and efforts to encourage the presence of Native Americans on campus back then than there are today,” the NATF said.

According to Foster, the overall budget for NASP at inception used to be around $2.1 million, adjusting for inflation. That budget has been drastically reduced over time.

“Where did Native studies go?” Foster asked.

What’s more is that UIC was once one of the leading universities for Native American enrollment, according to Foster. However, the NATF shows that NASP has increasingly struggled with recruiting and retaining students, which is often tied to the reduced budget.

As the NATF says, “Requests for budget increases are met with, ‘You don’t have enough students.’ Yet, as one interviewee suggested, how can you recruit the students if you don’t have the budget? How can you attract students if you don’t have the programming, the faculty and the relevant curriculum?”

NASP also faces challenges related to the limitations of the way they use funds. The University gives NASP some fee waiver money, according to Foster, but much of that money can only be used for in-state students.

“Most of our Native students tend to come from out of state, so I can’t actually offer my scholarships to most of my Native students,” Foster said. “I’ve been trying to get better support for out-of-state students.”

This lack of support for out-of-state Native students is especially egregious given the history of forced removal of tribes whose traditional homelands were in Illinois. The peoples of the Council of Three Fires: the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Bodéwadmi, as well as the Miami, Ho-Chunk, Menominee, Sac, Fox, Kickapoo and Illinois nations – a space of thriving communities that established a prosperous trade network before settlement – were displaced when the United States attempted to exploit the Chicago treaties of 1821 and 1833 to effect dispossession and forced removal of these sovereign nations. Today, Chicago is home to a populous and vibrant urban community of Indigenous Peoples in North America, with more than 65,000 Indigenous residents representing 175 different Nations. However, currently, there are no federally recognized tribes in Illinois, which limits the number of Indigenous students in Illinois that can use in-state tuition.

Joshongeva-Petersen also highlighted that in-state tuition excludes Indigenous folks from other places, which limits the impact of policy changes geared only towards students from federally recognized tribes.

“One of the shortcomings I think of that victory [with medical school tuition] is that I personally was trying to push more for in-state tuition for anyone of Indigenous background, including those that are from state-recognized tribes and also from the first nations in Canada and the various indigenous groups in Central America and South America,” Joshongeva-Petersen said. “Because one of the big strengths of our group is that we have a very wide variety of experience.”

Foster hopes that with student involvement and activism, UIC will be able to revitalize its resources for the Indigenous community and mitigate many of the issues they face. According to Foster, university leadership has been supportive of NASP’s desire for growth and has been responsive to their requests.

“I think the new leadership here is awesome,” Foster said. “But it always takes student engagement too.”

Foster highlighted the power that student activism and organizing have to uplift the Indigenous community, particularly at UIC, recalling how the start of Indigenous services at UIC was brought about by activism from community members.

“A lot of the things that happen at this university happen almost entirely because of student power,” Foster said.

Foster described NASP as a “student-driven activist project,” encouraging students to respond to the tremendous amount of work needed to “revitalize our university’s commitment to Indigenous students and be a good partner to the Native community.”

However, though student organizing can be rewarding, it also takes a lot of time, labor and energy, according to Joshongeva-Petersen.

“I’m proud that I helped get in-state tuition, but ultimately, if UIC wants there to be positive changes for their Indigenous students, UIC as an institution and UIC College of Medicine as an institution have to push for those changes themselves,” Joshongeva-Petersen said. “I feel like we’ve kind of laid down the groundwork for there to be more work to be done by the school, but it can’t just be us students because we’re med students and we’re already busy and resource-strapped.”

Despite this acknowledgment, Joshongeva-Petersen still hopes to continue his work in advocacy and education.

“One of the things I’m hoping to do this next school year is to actually start a lecture series in which I bring in various voices both from Indian country and also just radical voices who are trying to make change within our society,” Joshongeva-Petersen said. “Just to get a better sense of what it means to be Indigenous health leaders and also how to stand in solidarity and how to change these institutions that are ultimately failing our people.”

So, how can students support Indigenous organizations at UIC? “Come as you are” and get involved by coming to events, following Indigenous organizations on social media, getting involved in event planning and making connections between organizations, Harris said. Foster agreed that active participation is a valuable way to support Indigenous organizations on campus.

“I think the impression that a lot of UIC students think is that NASP is just for Native students, or these Native organizations are just for Native students,” Foster said. “But actually, these are organizations that allow you guys to interact with Indigenous people in Chicago and connect and back and relate, and you don’t have to be anything at all except for interested and engaged.”

Joshongeva-Petersen added that being an ally to the Indigenous community requires people to educate themselves by following Indigenous changemakers/activists and reading up on the dark sides of history, as well as getting out of their comfort zones in terms of advocacy.

“When I try and stand in solidarity with other people, I don’t necessarily consider anyone a real ally until they have done something that makes them uncomfortable in their allyship,” Joshongeva-Petersen said. “I don’t feel like I’m a full ally until I’ve stepped out of my comfort zone and tried to push for change – until I’ve taken that step.”